|

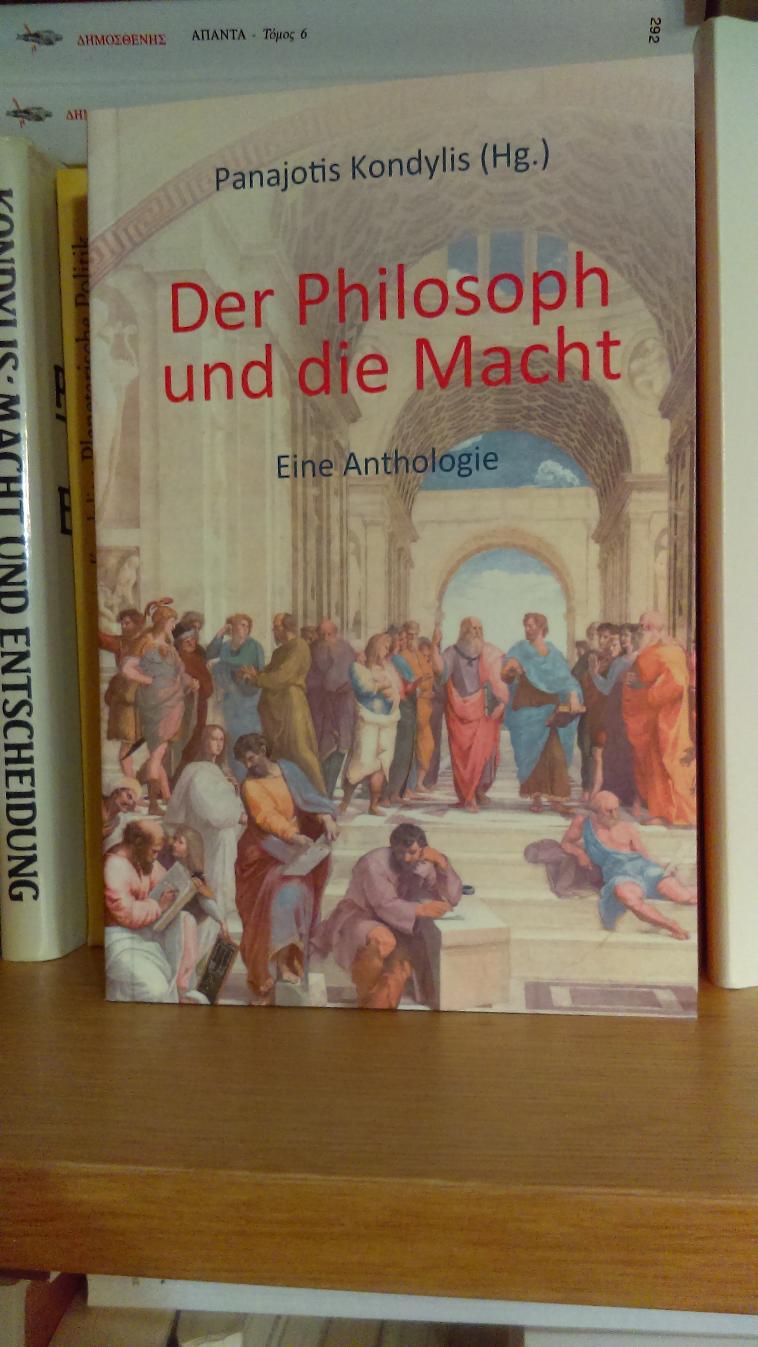

Introduction to The Philosopher and Power by Panagiotis Kondylis.pdf Size : 362.618 Kb Type : pdf |

"Irrespective of the reasons for its coming into being, philosophy has an effect only by legitimising power or dominance or related claims. Precisely this function belonging to it explains in the final analysis why it has until today for the most part devoted itself to the ethical coping with, transcending or taming of, the phenomena of power (i.e. with the assistance of ethical categories): only ethically legitimised power is able to exercise dominance, and only ethically legitimised power can support (or topple) an authority (a regime of dominance). Philosophy as such never talks of power unselfconsciously and impartially – that is, non-ethically, therefore without intentions in respect of power – but only very few philosophers did that. In our days, a freer tone indeed sometimes becomes audible, yet that is not due to a solution to, or untying of, the primordial bond between philosophy and ethical thought, but rather to the dissolution of the total traditional philosophical examination of themes and topics under the influence of the mass-democratic-postmodern thought style still being formed right now, in which everything may be combined with everything with a carefree and irresponsible nonchalance to do whatever one wants."

"When time-honoured, venerable institutions, or customs existing for a very long time, are thrown overboard without further ado, when the holy fetters of religion and of morals and ethics are suddenly ripped off, when even words change their meaning – then it becomes as clear as daylight that all this is artificial constructs, as well as statutes and institutions, not Nature."

"Of course, self-preservation has for its part a different meaning for the strong, who can only maintain his power by expanding it constantly, and for the weak, who saves himself by making concessions to the wishes and desires of the stronger."

"In Plato’s efforts to reduce sophistry to buyable, venal rhetoric and a technique of power, the antipathy of the aristocrat resonates against the morals and mores which, in his opinion, were brought into being after the rule of the demos, that is, against the irrational prevailing or unrestraint of reckless selfishness and lust for power, and, despicable, base hedonism. And although the structure of his philosophy does not least of all come out of his endeavour to confront and oppose sophistical anthropocentrism and relativism with ultimate, i.e. ontological and metaphysical arguments, he does not want to or cannot, nevertheless, take the Sophists completely seriously as thinkers. Thought, which revolves around power and striving for power, constitutes for him a superficial, frivolous theorisation of ruling and dominant democratic or tyrannical praxis, at any rate, philosophy it is not. "

"Where several parts should constitute a unity or whole, there a hierarchisation into ruling or dominating, and, serving, subservient or servile, must also take place, which is in the interest of both sides; the lower tiers of the hierarchy benefit from their being controlled by the upper tiers in exactly the same sense as the body or flesh benefits from its management, direction or control by the soul, or, the faculty of desire or the desirous part of the soul benefits from its guidance by understanding. This crossing over or interweaving of ontology and ethics for the legitimation of domination elucidates in itself how far away the thoughts world or ideological universe of ancient political philosophy is from the various kinds of self-evidence of our mass-democratic age. Should today the ethicisation of politics or the replacement of power by ethics as far as possible serves the dismantling of dominance, domination or authority, which is based on inequality, then the ethical shaping of politics meant for Plato and Aristotle the founding of authority as dominance exclusively on that inequality which emerges from the (normatively understood) nature of things. Equality in the newer anthropological sense is nearer to the perception of, or thoughts about, power of sophistry, however here also equality did not appear to be for instance a desirable social ideal or a recipe for the achievement of the common good or general bliss, but it meant that anyone can and is allowed to rule or dominate, only if he proves to be the most powerful or the most proficient and worthy. The thus unethically understood equality of course corresponded for its part with the anti-metaphysical underpinning and justification of inequality amongst men.

The almost complete extermination of sophistical literature as well as the full [[gapless]] handing down or transmission of the Platonic writings unequivocally answer the question of what the ideological options of organised societies must be and what ideational weapons cut, slice, chop the sharpest and hardest, or are most effective, in the social struggle for power."

"One does not have to specifically explain what impression thinking and theories of a sophistical provenance about power made on Christians. But the heathen or pagan hubris appeared to them just as impertinent, shameless and inexcusable when it arrived on the scene not as naked, blatant striving for power, but in the guise of the search and desire for honour, fame and recognition. Such striving for power was in the ancient Greek code of aristocratic ethics absolutely at the top and was also for the Romans, as a sign of true manliness, familiar and legitimate."

[[Substitute "God" with "Equality" or ...; "man" and "he" with "human" and "she" or "it"; "theological" with "ideological" if you want, and you get a situation which has not changed structurally or formally ever... the content simply changes...]]

"God’s omnipotence reaches in the history of ideas its zenith at the moment in which it is assigned [[God undertakes]] the task of distributing power and authority amongst men, and men are called upon to wield power and authority as dominance in the name of God. Consequently, God’s omnipotence becomes a political issue of the first order. Because it does not exclude the humble and meek from earthly, worldly office and dignity, it does not even abolish those important and sometimes or often also decisive spaces for wielding power, which are found away from office and dignity, but it forces humans in relation to that, to conduct their power struggles (nominally) on the terrain of the theological art of interpretation. The will of that all-mighty, omnipotent God, who alone can grant power, should now be interpreted; the powerful or the ruler is henceforth he who is capable of bindingly interpreting the will of all-mighty God."

"Hobbes and Spinoza still represent the New Times in their innocence. With that intellectual uprightness, rectitude and honesty, which presumably perhaps only solitary spirits can allow themselves, they draw from the basic ontological premises of new-times rationalism the ultimate conclusions, and in the intoxication of logical consistency, which as passionate thinkers thrills them and carries them away, they care little about the ethical scandal, which they put and set up in the world. That is why they must be turned into or regarded as philosophes maudits [[= (ac)cursed philosophers]], precisely when new-times rationalism, through the so-called Enlightenment, captured and embraced the broader educated strata and put its opponents on the defensive. To be pushed through and imposed socially, however, it had to energetically rid itself of, or repudiate and disclaim, the suspicion of nihilism, and outbid the theologians at the auction of values. If striving after power is seen as the fundamental anthropological given fact, then ethical relativism can hardly be avoided, since norms and values must be interpreted as functions of social power and social authority as dominance. That is why as a rule (i.e. apart from complicated exceptions in the history of ideas like for instance Kant), it has been thus: the more ethically engaged and involved Enlightenment thinkers operated or appeared in philosophical politics, the more intensely and fiercely did they put Hobbes and “pessimistic” anthropology generally under fire."

"... the Ought is no norm, which is extrinsic to the Is (Being) and as a result must bring the Is (Being) under its violence and force, control, authority, dominance, if it wants to be realised (this Enlightenment perception of the Ought would have to end in revolutionary terror), but the Ought inheres in the Is (Ought), it constitutes, as it were, the driving or motive force and the soul of the Is (Being). That of course sounds strange, because ..."

"Nietzsche’s incapability, despite all the delicate observations in the field of individual psychology, to apprehend the mechanisms of social power and authority as dominance concretely and against the background of a likewise concrete multi-dimensional anthropology, nourishes his belief in the possibility of a non-ethical-innocent power or in a prevailing of such power. Yet innocence was irrevocably lost already at the very beginning of culture; culture started with the adoption, assumption and acceptance of a meaning, and since then it reserves for the founder or donor, the custodian and protector or the interpreter of the meaning of things, the uppermost rank in the social hierarchy. The capacity, capability or function creating meaning and taking precautions for the future, that is, that which is called “spirit and or intellect” dynamises the biologically determined striving for, and drive of, self-preservation to an almost boundless extent, and turns such a striving for, and drive of, self-preservation into the striving for power of beings of culture or civilised beings, which unfolds, acts and fights first of all at the level of the aforementioned lies necessary for the preservation of life."

"During the execution of a decision taken, power as Can, i.e. an ability to do something, turns into the struggle for power, which for its part requires the distinction between friend and foe. Plessner stresses that the friend-foe-relation stretches or extends to all sectors of life, both to public as well as private, however, he simultaneously wants to call anthropology, which puts this relation at the centre of attention, a political anthropology. From that one must infer a very broadly understood concept of politics, whose dubiousness can only be hinted at here."

"Without making use of the term “power”, Kojève creatively made good use of Hegelian conceptuality and impressively outlined the question of power and of the power struggle. The tight connection of this question with the question of the human specific feature in comparison to the (rest of the) animal kingdom places here – differently to Nietzsche’s late ontological approach – the analysis entirely at the level of human culture and human history, whilst at the same time, the teaching or theory of drives, urges, impulses tacitly undergoes in part a modification, in part a neutralisation. In place of the drive, urge or impulse, namely desire steps in, which as such of course stems from man’s biological texture or composition, however, desire’s specifically human character leaves the animal element far behind, i.e. it goes way beyond the animal element, and even demands the sacrifice of the animal element (that is, biologically understood self-preservation). In the often seemingly futile, fruitless and useless desiring of that which others desire – and indeed simply because they desire it –, in the desire for recognition and in a prestige struggle of and for life and death, the human being is constituted as self-consciousness, and with him, History too, whose end, ultimate or final goal or aim must as a result be determined by this constitution of the human being.

Since for Kojève that which was acted out in our century [[= the 20th century]] materialised the end of History discernible already since Hegel and by Hegel, he could serenely follow and face the events and things that happened and derive no ethical concepts or conceptual plans and recipes from his analysis of the phenomenon of power."

"Arendt finds fault with the tradition of political thought for the ... very easy, uncritical identification of power and violence, without realising that this identification stems from a common and very familiar topos or commonplace of normativistic thought since Plato, who re-emerges in every contradistinction on every occasion of “good” or “just”, and, “bad” or violent wielding of power, and also underlies and inspires Arendt’s definitions of the concept of power (and of violence). In any case, she makes a gross mistake when she attributes the aforementioned identification to Max Weber. Because Weber does not connect or combine violence with power in general, but with the state and (authority as) dominance; for him, power in itself is amorphous, and as such is not an object or subject matter of sociological analysis, although he uses the term freely and loosely in order to outline or describe the aim of political struggle. If one overlooks the exercising of (authority as) dominance, one therefore defines power too broadly (“meeting of minds or agreement and understanding”), and violence too narrowly (“instrumentally”), then one can easily assert that power has nothing to do with violence, and violence does not in the least belong to, or characterise, the deeper essence of the politically organised collective (or community). Naturally, no polity or political community can survive, for a long time, the daily exercising of violence to a great extent, that is, the raging of permanent civil war,– however, just as little can a polity or political community exist without the constant threat of violence, without an internal organisation and division of labour which allows it to translate or turn the constant threat of violence promptly into action, i.e. the use of violence. High cultures or developed civilisations have hitherto hardly existed without the institutional exercising of violence, and that of course cannot be a coincidence. The constant threat of violence can indeed rest on the broadest “meeting of minds”, and as such is “power” in Arendt’s sense, yet on the other hand, the fact remains revealing and instructive for the character of political and social organisation, that hitherto no meeting of minds was achieved in regard to the opposite – that is, in regard to the renunciation or relinquishment of every threat of violence. The meeting of minds, upon which this organisation is actually founded in the long term, contains a limine the threat of violence and the possibility of the exercising of violence, as e.g. the daily detention or arrest of people proves in every state and country, without exception. Arendt’s saying that violence is or becomes applied where there is no power any more, constitutes, therefore, an empty or meaningless truism or tautology, which is based on definitional manipulation, namely, on the substitution of “(authority as) dominance” by “power”."

"The theoretically confusing and misleading, and historically-sociologically infertile effacement of the conceptual boundary between power and authority as dominance also characterises Foucault’s approach, although here the elimination of the concept of authority as dominance serves the convergence or approaching better than the contrasting of power and violence. Foucault is undoubtedly right with regard to his basic thesis that power is neither a massive essentiality (i.e. a self-contained and tangible entity or being), nor is it located or situated exclusively in certain political bearers, but it penetrates and permeates the whole of society and constitutes a net or network of relations or a correlation of forces. But that does not mean anything other than only that power in itself is amorphous and must be crystallised in innumerable, different forms. Underneath this crystallisation, i.e. if there is no such cyrstallisation, power can be the object or subject matter of anthropological and psychological, but hardly historical investigations; Foucault himself can in his search for, and investigation of, the microcosm of power, barely discover smaller particles than facilities (establishments or institutions) like the clinic or prison. With that, however, the problem just begins and is simply touched upon. Because there are greater and smaller, heavier and lighter, more complicated and simpler crystals of power, and the differences or the transitions amongst them require macroscopic analysis (too) in order to be explained. Foucault’s definition of the state as the institutional integration of power relations suggests that he has in mind an additive and quantitative relationship, and explains neither the social hierarchisation of power relations and of facilities and institutions, nor the existence of power relations outside of the institutional grip or control of the state – something of course which is due to the above-mentioned obliteration of the conceptual border between power and authority as dominance."

[[I wonder why Arendt and Foucault have been or still are "darlings" of the Academic Establishment in the English-speaking, and not only English-speaking, world, starting with the U.S.A.! How else could "Evil" and "Oppression" in social circumstances of historically unprecedented mass affluence - whilst "just happening to by-pass" particular forms of GROSSLY DISPROPORTIONATE power crystallisations in a certain very small minority group - be "Academically and Theoretically Justified"!!! Hahahaha!!! Personally, though, I'd say that there is at least some degree of merit in both their work, particularly H. Arendt's... the fact that the Homosexual has been much, much, much more of a "darling" than the German's Girlfriend probably says a lot too... grosso modo, the higher the overall standard of thought, the less of a "darling" one is... though on the question of "power", Foucault seems to have come closer to hitting the nail on the head than Arendt... (= translator's comment = nothing to do with P.K.)]]

"On the one hand, it was often disputed or doubted that striving for power belongs to human nature, if one means with that a primordial drive, urge or impulse for the absolute domination of other humans. Logically, however, it is not at all necessary to accept the existence of ineradicable and aggressive drives, urges and impulses of power in order to ascertain the always ubiquitous having an effect of the striving after power. To striving after power, the logic of the situations, in which social activity takes place in human societies, push – and this logic cannot be canceled out or abolished as long as humans are simply interested in their self-preservation. Culture and the, through culture, effected ideational redoubling, diversion and channeling or neutralisation of biological factors have turned self-preservation into a very complicated and multi-layered task, not least of all because they connected self-preservation and the question of meaning very tightly to each other."

"... the process of self-preservation, as Hobbes knew, is dynamised by means of the specifically human ability of imagining or picturing future situations and taking precautions for merely possible situations. One would have to accept a pre-established harmony of spirits(-intellects), that is of ways of thinking or mind-sets, of wishes and of passions, in order to exclude, under these conditions, conflicts, even extreme conflicts. That is exactly the reason why ethicists, moralists and moral philosophers want to pinpoint and behold the essence of man in his Reason, and over and above that, stress the uniformity and bindedness of the capacity for Reason in contrast to the many questions and matters of taste."